The Gambler at The Coronet Theatre

- 5 days ago

- 5 min read

On the auspicious date of Friday 13 February, I went to see The Gambler, performed by the Kyoto-based Chiten Theatre Company at the Coronet Theatre in Notting Hill. This adaptation of Dostoevsky’s novel was my first experience of Chiten’s work, so I was curious to see what they were all about.

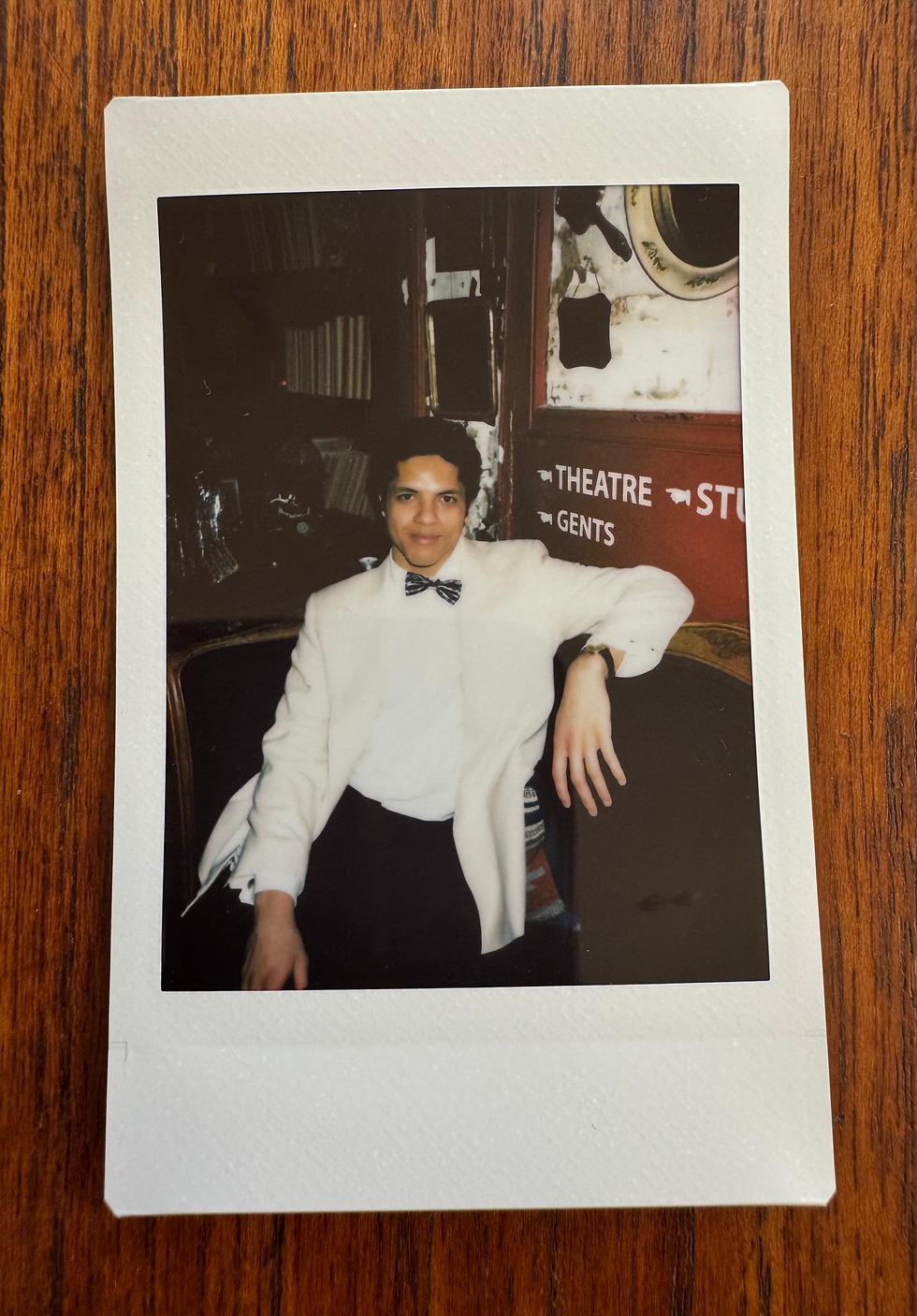

The Coronet Theatre is one of London's hidden gems. It first opened in 1898, and you can feel that history in the fabric of the building. Its candlelit bar, open before and after performances, has an old-world elegance which I admire. I had a drink there with a friend beforehand, and for a moment it felt as though we were sitting in the carriage of a sleeper train. The auditorium also has a distinctly nineteenth-century atmosphere, which felt perfectly suited to Dostoevsky’s fevered portrait of obsession and chance.

What I Was Curious About

A Russian novel interpreted by a Japanese theatre company for a London audience already felt like an interesting cultural journey.

I was curious how, under the direction of Motoi Miura, that translation would manifest on stage. Would it feel culturally specific or deliberately neutral? Would it lean into stylisation or psychological realism?

What Stayed With Me

More than anything, it was the music that stayed with me.

Two musicians stood on either side of the stage with electric guitars, performing live throughout. They were fully visible, framing the action. The soundscape pulsed with distortion, electronic textures and fractured beats, giving the performance a strong sense of momentum.

There was something in it that felt distinctly Japanese yet undeniably European. A synthesis. It felt intentional and precise, not like generic theatre underscoring. It shaped the atmosphere rather than simply decorating it.

During the curtain call, one of the musicians held up an LP. As I left the theatre, I saw it displayed at the bar. The score had been composed specifically for this production by none other than Ryuichi Sakamoto. That made immediate sense. The clarity, the restraint, the architectural quality of the sound. It felt as structurally important as the text itself.

The costumes also caught my eye. They were beautifully conceived, European silhouettes carefully tailored in fabrics that caught the light without shouting. A morning tailcoat and bow tie. A silk jacket and skirt for the wealthy aunt. The ensemble looked beautiful under the lighting.

There were small moments of friction. The General’s costume felt slightly under-articulated, and at times his status was not immediately clear.

More noticeably, the performer in the black turtleneck and heavy wool overcoat carried by far the most physically demanding role. He was constantly running, pushing actors seated at the long table, dancing, delivering text at full intensity. Under the stage lights, in such heavy layers, the strain quickly became visible. Sweat poured down his face, at times dripping onto the actors around him.

I found it difficult to ignore. Rather than intensifying the drama, it made me feel slightly uncomfortable, acutely aware of how physically taxed he must have been. When a role demands that level of sustained exertion, I could not help wondering whether the costume might have been made from lighter fabrics. The aesthetic was strong, but it felt as though the design did not entirely serve the body required to sustain it.

Where I Felt Resistance

Where I felt resistance was in the energetic register of the piece.

The performance ran for over two hours without an interval and sustained a very high intensity throughout. Much of the text was delivered at full volume, often shouted, with constant fast-paced physical movement. The commitment was undeniable. The energy rarely softened.

For me, the lack of modulation became difficult to stay with. When tension does not shift, it can begin to flatten. I found myself craving contrast. Quieter passages. Stillness. Moments of interiority where the breath could settle before being pulled tight again.

A shout is more piercing when preceded by silence. Without that variation, I felt a subtle tension in my own body as an audience member.

I also found it difficult to follow the narrative. I had not read the novel beforehand. While the production made me curious to read Dostoevsky, I struggled to grasp the relationships and stakes in the moment. There are many characters, many cultural and social references, and the delivery was largely front-facing rather than dialogic.

Combined with subtitles and sustained intensity, I occasionally felt a step behind.

Ideally, a play shouldn’t require prior reading in order to follow what’s happening. Familiarity can deepen appreciation, but it shouldn’t be necessary just to understand the basic shape of the story. I admired the aesthetic ambition, but at times I struggled to connect emotionally.

What It Stirred In Me

If there is one clear takeaway for my own work, it is the power of the sonic world.

The presence of a composed, intentional score gave the production depth and identity. It reminded me how fundamental music can be. In my own practice, whether in opera, ballet, or Kabuki-inspired theatre, music often feels like the true spine of a piece. This encounter reaffirmed that instinct.

It also reinforced something I’ve felt for a while. When theatre relies too heavily on text, it can start to feel more like explanation than experience. Some of the most powerful moments in this production were silent, such as the revolving casino table and the actors held in suspended tableau. In those images, relationships were made visible through spacing and posture rather than words.

It reminded me how much theatre can learn from forms like Kabuki and ballet, where gesture, rhythm and composition carry narrative weight in the absence of spoken language. There is something economical and potent about trusting the body and the image.

If anything, the evening clarified my own direction. I want music and movement to carry equal weight with text, to trust stillness, and to allow silence to speak.

How I Felt Walking Out

When I left the theatre, I did not have a single clear-cut emotional reaction.

I did not walk out in a state of simple amazement, nor confusion, nor pure exhilaration. It was something more layered. I felt that I needed to process what I had seen.

Now, with a few days’ distance, I reflect on it mostly very positively. They tackled an extraordinarily complex and psychologically intricate novel in The Gambler. They made bold choices. They did not hold back. The set, the costumes, the score, the sustained physical intensity all spoke of confidence and conviction.

Ultimately, I found it inspiring to see young artists from Kyoto travel to London and present their work with such courage and ambition. To take on a work of this scale, collaborate with a composer like Ryuichi Sakamoto, and shape it into something visually elegant and sonically distinctive is no small task.

The Gambler’s London run concluded on 15 February, and I am glad I caught it while it was here.

My thanks to Chiten Theatre Company and their creative team for bringing this production to London.

Direction: Motoi Miura

Producer: Yuna Tajima

Translation: Ikuo Kameyama

Music: kukangendai

Cast: Takahide Akimoto, Midori Aioi, Yohei Kobayashi, Satoko Abe, Dai Ishida, Masaya Kishimoto, Shie Kubota

Set design: Itaru Sugiyama

Costume design: Colette Huchard

Lighting design: Yasuhiro Fujiwara

Sound design: Bunsho Nishikawa

Stage manager: Atsushi Ogi

For more information about Chiten Theatre Company, visit: https://chiten.org/en/

Comments