When Silence Speaks: Discovering the Japanese Art of Benshi

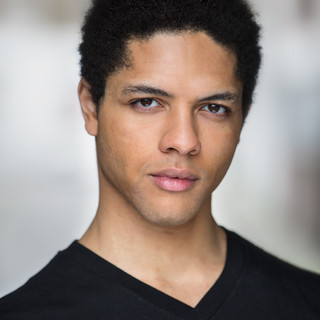

- Suleiman Suleiman

- 3 days ago

- 8 min read

Updated: 3 days ago

I recently discovered the art of Benshi, or silent film narration, at a one-night-only event called MIC! PROJECTOR! ACTION! at Regent Street Cinema in London. Held on 20th November, the evening featured performances by Guy Perryman, a Tokyo-based radio DJ, voice actor, and writer, and Koyata Aso, a renowned Benshi artist.

I was curious. I had never experienced Benshi before, and a friend, George Crosthwait, had suggested it might resonate with me. The idea of a Japanese art form blending silent film with live performance immediately caught my attention, especially as I create my own Japan-inspired, multi-disciplinary events. I expected something quite formal, and imagined the narrator’s presence would be felt solely through their voice.

Instead, I found myself drawn into something far more dynamic. Guy and Koyata were more physically expressive than I expected, creating a surprisingly intimate connection with the audience. It was as if film and live performance were unfolding in the same breath.

I left the cinema eager to understand more. Benshi is over a century old, yet it remains surprisingly unknown, even among many of my Japanese friends. Koyata Aso is a pioneering Benshi performer, and it was a pleasure to speak to her about her craft, which she has honed for over 30 years. Before we step into the conversation, here is a brief introduction to the art of Benshi.

What is a Benshi?

A Benshi is a live performer who stands beside a silent film, bringing it to life through their voice and imagination. They act as narrator and master of ceremonies, explaining the story, speaking for the characters, and creating a rapport with the audience.

Silent films reached Japan at the turn of the twentieth century. The Lumière brothers had first introduced moving pictures to Paris in 1895, and then to the UK at Regent Street Cinema in 1896. When these Western films arrived in Japan, they had no sound, no subtitles and many unfamiliar cultural references, so humans were needed to guide audiences through what they were seeing.

Japan has an impressive tradition of live narration in theatre. For example, Kabuki has its chanting and musical storytelling; Bunraku (puppet theatre) has its tayū, the powerful narrators who voice every character; Noh has its chorus. The Benshi grew naturally out of this wider culture of spoken performance. At first they were interpreters who translated foreign intertitles and explained the plot. But very quickly they became artists in their own right. Their comedic timing, vocal range, style and interpretation elevated the experience of watching a silent film.

The silent film era spanned from the 1890s to the late 1920s, but in Japan it endured well into the 1930s. Benshi thrived throughout this period, becoming an essential part of the cinema experience. At their peak, there were an estimated seven thousand Benshi performing across the country. Their presence was so beloved that audiences were reluctant to give up the living voice that guided each story. When sound films finally took hold, the art form began to fade. Only about twenty Benshi remain today.

My First Encounter with Benshi

I was caught off guard by the playfulness and artistic freedom within Benshi. Guy and Koyata both demonstrated astonishing vocal command, yet it was their improvisational skills that stayed with me. I had grown accustomed to the strict customs of traditional Japanese arts like Noh, Bunraku, and Kabuki, which can sometimes feel distant or inaccessible. Benshi felt different. Rather than maintaining that distance, Guy and Koyata created a direct connection with the audience. They watched the film with us, responded to it with us, transforming the cinema into a communal experience rather than an individual one.

Finding new ways to synthesise film and live theatre is something I continually strive for. These forms are often seen as distinct, yet Benshi brings them into a unique and compelling dialogue. It calls for a performer who can shift fluidly between roles — narrator, actor, guide, comedian, historian, host. As a performer, I’m always looking for ways to close the distance between myself and the audience. Benshi seems to do just that. It’s not about disappearing into a character; it’s about stepping forward, letting your personality and sensibility shape the tone of the evening.

There was a time when Benshi were stars in their own right. Their names sometimes outshone the films themselves. In photographs of Koyata and her father, the great Yata Aso, there’s a quiet glamour: tuxedos, tailored suits, crisp white shirts, bow ties. The visual style speaks of a Western refinement, yet it’s deeply embedded in a Japanese tradition. That meeting point—where cultures intertwine—is something I keep returning to in my own work.

Koyata Aso

Style was very much on my mind when I saw Koyata step onto the stage.

She wore a striking white feathered jumpsuit with silver metallic leather boots — a look that was both elegant and playful. During the Q&A, I asked her about her sense of style, and later, when we met in person, I was taken by her sincerity and down-to-earth warmth. The outfit made a bold visual statement, but one that sat naturally alongside her gracious and grounded presence. She spoke with such sincerity about what it meant to perform in London, a dream she had held since childhood.

It was Koyata’s first time in the UK, and she said she was relishing every moment of it. She also spoke lovingly of her artistic heroes, Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, whom she has studied since childhood. Though she was flying back to Tokyo the very next morning to perform, she generously took the time to speak with me after the show.

Koyata has been performing Benshi professionally since the age of ten. For someone with such a long and accomplished career, she spoke with striking humility. There was a quiet determination about her—a sense that, even after decades on stage, she was still committed to growing as an artist. What follows is our conversation, reflecting on her London debut.

In Conversation with Koyata Aso

SULEIMAN:

You’ve been performing Benshi since you were ten years old. Was there a particular moment or influence that first made you think, “Yes, this is the path I want to follow,” when you began your journey as a Benshi?

KOYATA:

It wasn’t something that happened all of a sudden. I gradually came to feel that I wanted to become a Benshi. I was actually a very quiet child who hardly spoke at all. My favourite phrases were “either way is fine” or “I don’t mind.”

From the time I was about two or three years old, I watched Chaplin and Keaton films, and I also watched my father performing on stage, moving people’s hearts through his performance.

I grew up thinking, “I could never do that, but my father is amazing.” When I was nine years old, I finally gathered the courage to tell him, “I want to be a Benshi like you.” At first he said, “Don’t be ridiculous! Get out!”

But I kept asking him every day, even while he was taking a bath or using the washroom (laughs), and eventually he agreed — on the condition that I would “practise every day” and “continue for at least five years.” That’s how I became his apprentice.

SULEIMAN:

Your father’s legacy is such an important part of your journey. Is there a particular piece of advice or wisdom he gave you that has stayed with you throughout your life?

KOYATA:

What I’ve learned from my father is that living sincerely — and facing films with sincerity — is at the heart of the Benshi art. His storytelling and presence on stage are truly powerful, but what I admire most is the deep love in his heart.

No matter how tragic or frightening a film may be, when my father narrates it, there is always love in his voice. Somehow, after watching, you feel a small sense of comfort or hope. It’s a mysterious quality, something I’ve not yet reached, and perhaps may never fully reach.

I believe Benshi, like many other art forms, is an art of polishing the heart. On stage, my father often teaches me to think deeply about the emotions that fill even the silent moments between lines. From Chaplin’s films especially, I’ve learned about “unconditional love,” and I try to add my own experiences, thoughts, ideals and imagination to that feeling when I perform.

SULEIMAN:

Now that you’ve had a little time to reflect on your first Benshi performance in London, did the experience give you any new perceptions about your craft or spark any ideas about what you’d like to develop moving forward?

KOYATA:

London has always been a place I admire because it’s the birthplace of Charlie Chaplin. I’ve never known anyone who expressed love so purely. To follow his example, I’ve tried to live sincerely and stay true to myself. In that sense, Chaplin is my lifelong role model.

Performing Benshi in such a historic and dignified theatre in London was a great honour, and I’m deeply grateful for the experience. It reminded me that the path I’ve believed in was never wrong.

A Benshi performs live because there’s a special magic only a live voice can bring. It gives energy to the film and makes people feel excited and happy. The warm reactions from the London audience made me feel that this way of performing truly connects, and I want to keep moving forward with that belief.

SULEIMAN:

You seem to have a distinctive personal style. How do you feel your sartorial choices influence the way you narrate and connect with the audience?

KOYATA:

When it comes to fashion, I always think about the balance of the whole stage — how both the Benshi and the screen can complement each other visually. In everyday life, I’m not particularly fashionable, but on stage I want to create a look that feels lively, elegant and unified with the screen.

For over twenty years, after my debut, I performed in a single white tuxedo to honour tradition. But now I choose outfits that let me enjoy performing the most, because when I’m having fun, the audience can feel it too.

The only brand I truly love is ISSEY MIYAKE, and for this performance (in London) I wore one of my favourite pieces from their collection.

SULEIMAN:

Is it true that Kabuki actors were the original Benshi performers? Could you share a little more background about the connection between Kabuki and Benshi, and how that relationship shaped the early style of film narration?

KOYATA:

It’s actually a bit misleading to say that Benshi were Kabuki actors. There were cases where Kabuki actors became Benshi in the very early days of film narration. Before dedicated cinemas existed, films were first shown in Kabuki theatres, so collaborations with Kabuki music — such as Nagauta, Tokiwazu or Kiyomoto — occurred naturally. In that sense, Kabuki and its speaking style may have influenced early Benshi to some degree.

However, Benshi narration was also shaped by many other Japanese performing arts: rakugo, kodan, rokyoku, shingeki, shinkokugeki, mimicry, political speeches and even religious storytelling. Over time, elements from all these speaking traditions blended and evolved, and through this process the distinctive narrative art of Benshi was born.

SULEIMAN:

That’s extraordinary.

This year you celebrated 30 years as a Benshi performer. Looking 30 years into the future, where do you imagine Benshi might be? Do you think it will still be thriving in its traditional form, or do you see it transforming with new technology or styles?

KOYATA:

Thirty years from now, I think I’ll still be living freely and doing what I love — just as I do now. While Benshi is undeniably a part of Japan’s cultural tradition, I believe it’s also important to explore new forms of expression alongside passing down the art from master to student.

I started performing English Benshi because I wanted to share this art with more people around the world. I hope to continue meeting people, building connections, and broadening my perspective through those encounters.

To tell you the truth, I believe that Benshi is a universal performing art. To convey its energy and excitement, I’m always experimenting with new ideas. It may have originated in Japan, but I think it could have emerged anywhere in the world. That’s why I’d love to travel, collaborate with artists from different cultures, and explore what Benshi might look like if it had been born in their countries. That kind of creative journey would make me very happy.

SULEIMAN:

What piece of advice would you give to someone who feels inspired to explore Benshi and wants to pursue this path seriously?

KOYATA:

First, focus on building your voice and learning to speak naturally from your whole body. The basics are the key. And always live with sincerity and an open heart — keep growing and refining your inner self.

_______

Heartfelt thanks to Koyata Aso and Guy Perryman.

Follow them on Instagram:

Comments